<< If you’re here to find out how to arrange an illumination exhibit, workshop or lessons, please contact my speaker’s agency HERE. >>

* Quirky Content Warning!

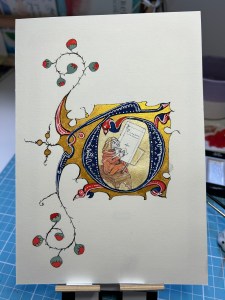

Painting illuminated letters and images and poring over the art of medieval manuscripts is a pretty niche obsession, so buckle up while I expound upon the skill, the history, and the GOLD…

I spent a year working my way through the English alphabet, one letter each fortnight. I invested countless hours to reading books on the art form and cataloguing illuminated letters and images to copy on Pinterest. Initially, my #illuminatedletteringchallenge was an attempt to become more consistent with my art practice. By the time I finished, it was that and so much more.

Why the Heck?

I mean, it’s so hard, right? All those itty-bitty details?

And it’s weird – really weird. Medieval manuscripts teem with hybrid beasts, cheeky monks, toilet humour, marauding snails, and political satire all right alongside sacred texts. So yeah, the weirdness is plentiful and delightful. Scriptures are serious stuff, but they made room for playfulness, and I think that is one aspect that intrigues me.

Art provides a brain break from my writing, and illumination is an exercise in deep focus. It is contemplative and slow – but it’s also a literal pain in the neck. Sometimes I wonder why I do this art form, especially when my neck and back are killing me and I’ve given myself eyestrain and a migraine from working so small. I almost gave up but then I decided to just work larger.

The better, less whingy answer to the whys and the what-does-this-have-to-do-with-children’s-books is this: the art of illumination is the perfect intersection of books, art, and history – all things l love bound together in gorgeous, gold-studded, richly coloured glory.

That is not to suggest that my work at this stage is “glorious.” It’s not (yet), but I’m learning and progressing nicely, thank you, and now that I’ve graduated to more costly materials, namely 23-karat gold leaf and imitation parchment, I’m motivated to keep improving.

Right now, about two years into this art practice, I would describe my lines as “organic,” which sounds more acceptable than “wonky.” I’m okay with organic and everything that entails. In fact, I embrace it. My wiggly lines and splatters are proof of the human behind the art…

Rather than a machine.

Sticking It to the Machine.

Illumination is my quiet act of resistance against the rise of AI and its attempts to take over the arts – visual, written, musical, and more.

Before the invention of Gutenberg’s printing press, illuminated manuscripts were painstakingly copied by hand on vellum (calf skin). Every step, from stretching the hide to lining the folios to making the size to stick the gold involved human labour, which makes their creation the antithesis of AI art. Illuminated books were laborious, costly, and time consuming, meticulously created by hand (or more precisely hands, as many people contributed); AI is virtual and instant, an impressive jumble of pixels combined by some energy-chewing, algorithmic super-computer in the aether.

Photoshop and graphics generators have conditioned us over the decades to see and expect sleek, pristine images, signs, and logos. It makes me think of how children are conditioned to prefer the “Disney aesthetic,” polished and commercial but soulless. (I bet that opinion gets some pushback.) It’s perfectly slick, but the art screams “machine-made.”

Nowadays we eschew organic lines and less-than-symmetrical images. We’ve lost our preference – and appetite – for signs of humanity.

No Soul, No Art

Art should hum with humanity, and that’s what I feel when I look at medieval manuscripts. I can’t help wondering about the artists who laboured over the works. Did they feel pride in their work or did they feel like indentured servants to greedy masters? How did they cope with sore backs and cramped hands? How were their scriptoriums lit? Were the scribes’ and limners’ acts of cheekiness in the margins celebrated or punished, and were they acts of rebellion against the system or intentional exercises in not taking their work too seriously?

All these questions bubble up as I copy their work using modern tools and materials, like pens, bleed-proof white paint, and synthetic parchment. (Thankfully, no animal has to die for my art.) My studio is comfortable and sunny, and my time is my own, so I doubt I will ever truly capture the soul that imbibes their art.

But I’ll enjoy the process anyway. I mean, who can’t love working with gold? With practice and luck, some of me will hum around the edges of my work. If I ever reach that stage, of suffusing a wisp of my soul to a work , I’ll feel accomplished.

This soul is hard to quantify, but we all know it when we see it – or rather, don’t see it, which is commonplace now that we’re wading through the soulless sludge of AI images (and texts and music).

My Resources

Pinterest has provided a treasure trove of medieval illuminated art images to study and learn from. I’ve sifted through thousands of images, looking for designs that sparks my curiosity or feature a style or element I’d like to attempt. I’ve catalogued them alphabetically, so feel free to check out this resource on my board, Wannabe Scribe.

(N.B. >> I’ve collated mostly historical public domain images, but some modern reproductions are so good it’s hard to distinguish them. This is problematic because the artists aren’t always listed, and I would of course like to credit them if I could.)

Sharing the Love of Illumination

I would love to provide an enrichment activity for history class, a gilding workshop, or an art display for students or adults. Please contact me via my speaking agency or email me at / scribed dot scriptorium at gmail dot com /. I can provide testimonials if required.