My grandfather called me Snoopy. It was my fondness for rummaging through cobwebby corners of his house that earned me the moniker. No closet went unexplored, no drawer unrifled, no crawl space unprobed.

The attic at Poppy’s house beckoned, otherworldly—icebox cold in winter and oven hot in summer with dust that rimed surfaces like post-apocalyptic frost. One day, nosing into an ivory garment bag, I came face to face with my mother’s wedding gown. Below it, a compact green train case conferred a pair of viciously pointy stilettos in pink silk—both excellent finds that kept me amused (and well dressed) for days. Another exploration unearthed the mother lode, a box labelled, ‘For Alison’ in my late grandmother’s scrawl. Nestled in layers of crumpled newspaper were an old-fangled sugar bowl, milk jug, and trifle bowl. Snooping, I learned, paid off.

The attic at Poppy’s house beckoned, otherworldly—icebox cold in winter and oven hot in summer with dust that rimed surfaces like post-apocalyptic frost. One day, nosing into an ivory garment bag, I came face to face with my mother’s wedding gown. Below it, a compact green train case conferred a pair of viciously pointy stilettos in pink silk—both excellent finds that kept me amused (and well dressed) for days. Another exploration unearthed the mother lode, a box labelled, ‘For Alison’ in my late grandmother’s scrawl. Nestled in layers of crumpled newspaper were an old-fangled sugar bowl, milk jug, and trifle bowl. Snooping, I learned, paid off.

In search of more treasures, labelled or otherwise, I ventured due south. Poppy’s basement brimmed with mysteries and monsters, such as the deadly Electric Wringer. “Stand back Snoopy, or she’ll slurp you up, squish you flat as a pancake, and spit you out the back,” Poppy yelled over noise, prodding the mangle with a pole, as if daring it to strike. I stood clear, watching the grinding, sloshing violence of washing day from a safe distance.

In search of more treasures, labelled or otherwise, I ventured due south. Poppy’s basement brimmed with mysteries and monsters, such as the deadly Electric Wringer. “Stand back Snoopy, or she’ll slurp you up, squish you flat as a pancake, and spit you out the back,” Poppy yelled over noise, prodding the mangle with a pole, as if daring it to strike. I stood clear, watching the grinding, sloshing violence of washing day from a safe distance.

It was from that secure vantage point that I discovered the basement’s cave of wonders. Poppy had converted the dark space under the stairs into a display case to hold souvenirs and curios from his globetrotting adventures. Tucked in its shadowy nooks were decades worth of accumulated stuff, dense with memories and oozing my grandfather’s legendary sense of humour. In my seven-year-old mind, I’d hit pay dirt. My mother, ever the modern minimalist, muttered about dust-collecting junk.

Naturally, I wanted to keep everything in Poppy’s fusty cabinet, especially the kitschy ceramic Three Wise Monkeys (macaques) from Japan. To this day, when I come across, ‘See no evil, hear no evil, speak no evil’ my mind beelines to Poppy’s basement. There were ashtrays from cruise ships, beer steins from Bavaria, and Venetian glass beads. Multi-limbed Buddhas from the Orient subleased space to a shocking array of pissing boy figurines and other toilet-themed curios. From Istanbul or Cairo or Timbuktu, a brass oil lamp, dull with tarnish, hinted at a resident genie. But the best curio by far was a tiny corked bottle that held a wisp of yellowed cotton and a tiny nugget, a flake really, of Klondike gold. I begged Poppy shamelessly for that little bottle (no fool was I, even at age seven), but alas, no. It was special—a souvenir from his father-son Alaskan escapade with my Uncle Connie.

Cabinets of Curiosity

Looking back with adult eyes, I recognise the display shelf for what it really was: my Poppy’s wunderkammer or cabinet of curiosities, a rather antiquated hobby. These visual encyclopaedias started as cabinets, but over the centuries they grew into immense collections that stuffed entire chambers full of oddities–dinosaur bones, rare butterflies, saints’ fingers, alchemists’ tools, stuffed animals, mummies, and more.

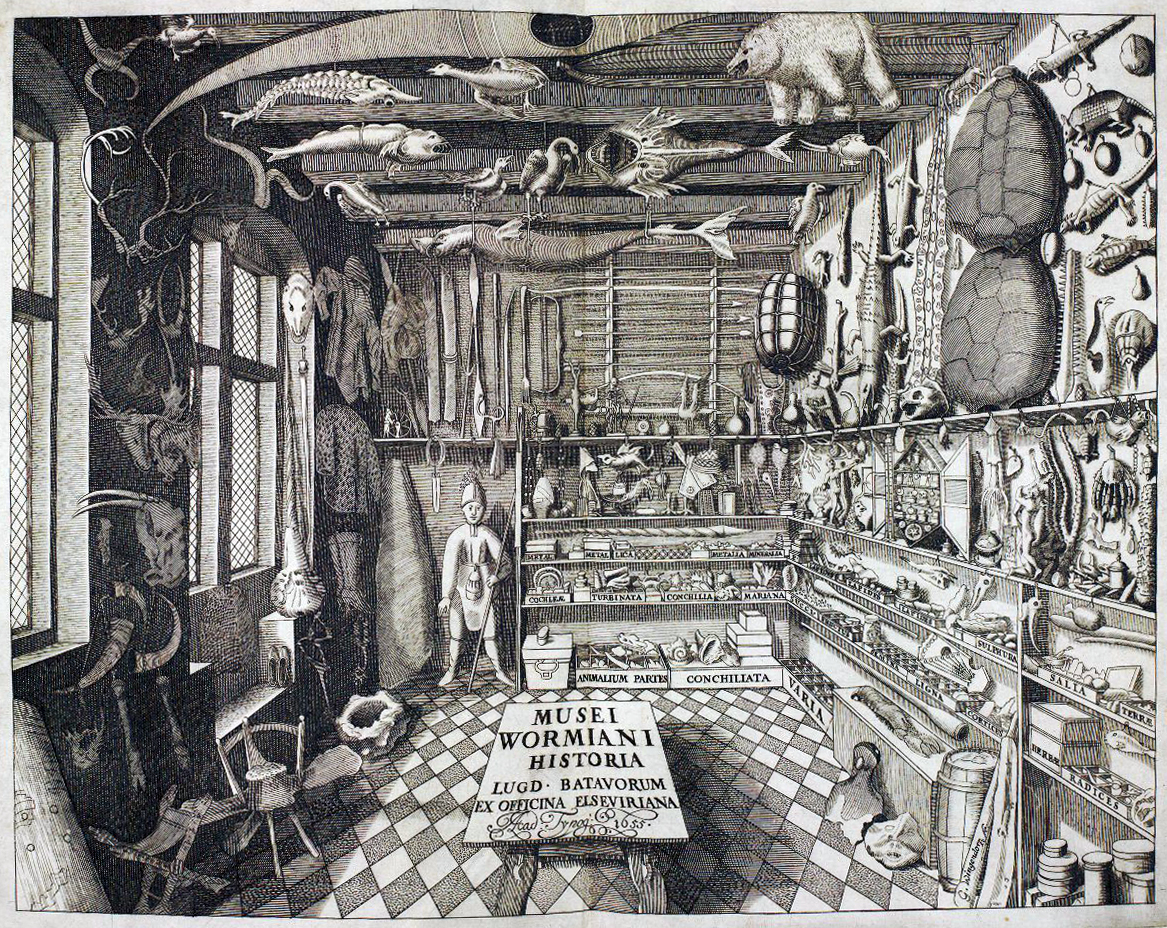

Wunderkammern (chambers of wonder in German) are first cousins to both the modern museum and the modern sideshow. In the 17th, 18th and early 19th century, European nobles vied to outdo one another with impressive, comprehensive wunderkammern. The collections intermingled science with superstition, as the world grappled with emergent empiricism.

Part one-upmanship for the über-rich, part scholarly enquiry, the collecting and displaying hobby led to important scientific and cultural advancements. Ole Worm, the Danish scholar and collector who created the Wormianum Museum (1655, shown above), debunked the unicorn tusk trade, showing the tusks (worth a king’s ransom) belonged to male narwhals not mythical creatures. He also disproved the weird but widely held notion that lemmings spontaneously generated and fell from the sky in stormy weather.

Peter the Great’s Kunstkamera, which was heavy on anatomical specimens and pickled foetuses, was intended to shift common people’s superstitions about genetic abnormalities, from devil-spawned monsters or divine punishment to mere accidents of nature.

The Outworking of Imprinted Memories

With the wunderkammer of my childhood imprinted on my psyche, it’s little wonder these eclectic collections continue to fascinate and make regular appearances in my writing. For unknown reasons, my villains tend to be collectors—greedy, predatory amassers of curios, artefacts, and specimens for their wunderkammern. Here are two examples.

In my MG | Gaslamp | Fantasy |Adventure The Temple of Lost Time, Lord Godfrey serves as both Royal Antiquary and Head Henchman. As the king’s advisor on Olden Magic, he leads the quest to find the legendary Temple of Lost Time. Godfrey believes the temple’s magical elixirs will reverse the dying king’s illness. Following fragments of ancient maps, Godfrey sets sail armed with his fully portable Cabinet of Magical Curios. Little does he know, stowed away in the ship’s hold is his nemesis, eleven-year-old Toby, who’s running for his life in search of his missing father…

Curiosity Cabinets for the 21st Century

One of my favourite forms of procrastination is snooping through Pinterest, which is basically a limitless, digital wunderkammer. Pinterest lets me have All The Curios without the dust and storage issues! Yay! I don’t use Pinterest as much as I used to because it’s full of annoying ads nowadays, but the promise of personalised curation remains: Create classifications (boards), hunt for ‘specimens’ (images and content), arrange, display, and share.

The Real McCoy – Melbourne’s Wunderkammer

So, back in May 2018, I was in Melbourne for KidLitVic, a conference for writers and illustrators of children’s literature. As my writing buddy Kellie Byrnes and I were walking down Lonsdale Street one night, we passed a street level window that made me stop and back up. The window revealed a human skeleton reclining, feet casually crossed, in an antique dentist’s chair. I’d stumbled upon a real cabinet of curiosity! Wunderkammer is delightful and quirky—and it’s situated in a basement, just like my Poppy’s!

So, back in May 2018, I was in Melbourne for KidLitVic, a conference for writers and illustrators of children’s literature. As my writing buddy Kellie Byrnes and I were walking down Lonsdale Street one night, we passed a street level window that made me stop and back up. The window revealed a human skeleton reclining, feet casually crossed, in an antique dentist’s chair. I’d stumbled upon a real cabinet of curiosity! Wunderkammer is delightful and quirky—and it’s situated in a basement, just like my Poppy’s!

Of course I had to go in for a serious bit of snooping through its fabulous displays. (The cabinetry alone is beautiful.) Wunderkammer showcases a variety of curios and natural wonders, including medical & surgical tools, minerals & fossils, insects & butterflies, taxidermy, globes & maps, and ephemera. Items are for sale, and business is delightfully brisk. Many thanks to the fine folks at Wunderkammer, who kindly allowed me to snoop to my heart’s content and take photos. I highly recommend a visit next time you’re in Melbourne: 439 Lonsdale Street, Melbourne.

Image Credits:

- Attic photo by Kevin Noble on Unsplash

- Basement photo by Timothy Rhyne on Unsplash

- 3 Wise Monkeys photo by Joao Tzanno on Unsplash

- Musuem Wormianum via Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain

- Wunderkammer photos by Ali

Interesting Links:

Artist Rosamund Purcell’s recreation of Museum Wormianum is a permanent installation at the Natural History Museum in Denmark. The display includes 40 of the artefacts from Worm’s original Wunderkammer.

Cabinets of Curiosity became quite trendy about five years ago.

Leave a reply to Peter Taylor Cancel reply